UNO reverse card: stealing cookies from cookie stealers

Criminal infrastructure often fails for the same reasons it succeeds: it is rushed, reused, and poorly secured. In the case of StealC, the thin line between attacker and victim turned out to be highly exploitable.

StealC is an infostealer malware that has been circulating since early 2023, sold under a Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) model and marketed to threat actors seeking to steal cookies, passwords, and other sensitive data from infected computers. Like many MaaS offerings, it comes with a polished web panel, campaign tracking, and just enough operational security to appear professional.

In the spring of 2025, the group developing the StealC malware had a rather eventful few months. The group released a new major version of their malware, moving from StealC_v1 to StealC_v2. Almost immediately after the release, their web panel leaked. Following that, TRAC Labs published a blunt technical teardown questioning the quality and maturity of the malware titled, Autopsy of a Failed Stealer: StealC v2.

What didn’t make headlines at the time was arguably far more damaging. While analyzing the leaked panel code, we identified a vulnerability that allowed us to observe and interact with StealC operators themselves. By exploiting it, we were able to collect system fingerprints, monitor active sessions, and—in a twist that will surprise no one—steal cookies from the very infrastructure designed to steal them.

In this blog post, we’ll cover a specific threat actor and demonstrate how much can be learned by exploiting vulnerabilities in the threat actor’s infrastructure.

This research is based on analysis of publicly available information and leaked artifacts widely accessible within the security community. It was conducted for defensive and educational purposes. CyberArk Labs shares this work to support responsible security research and improve the community’s understanding of real-world threats.

Exploiting a simple XSS vulnerability in the StealC MaaS panel

The StealC web panel gave researchers a rare glimpse into the backend of the malware operations. It didn’t take much effort for us to find a simple XSS vulnerability in that panel. We won’t share specific details of the vulnerability itself to avoid helping the StealC developers patch the issue or enabling any would-be StealC copycats from using the leaked panel to try to start their own MaaS.

By exploiting the vulnerability, we were able to identify characteristics of the threat actor’s computers, including general location indicators and computer hardware details. Additionally, we were able to retrieve active session cookies, which allowed us to gain control of sessions from our own machines.

Given the core business of the StealC group involves cookie theft, you might expect the StealC developers to be cookie experts and to implement basic cookie security features, such httpOnly, to prevent researchers from stealing cookies via XSS. The irony is that an operation built around large-scale cookie theft failed to protect its own session cookies from a textbook attack.

In the next couple of sections, we’ll focus on a single StealC operator we’ll refer to as YouTubeTA, an abbreviation for YouTube Threat Actor. We’ll start with their malware campaigns and then detail what the XSS exploit revealed about their identity.

StealC malware campaigns abusing YouTube accounts

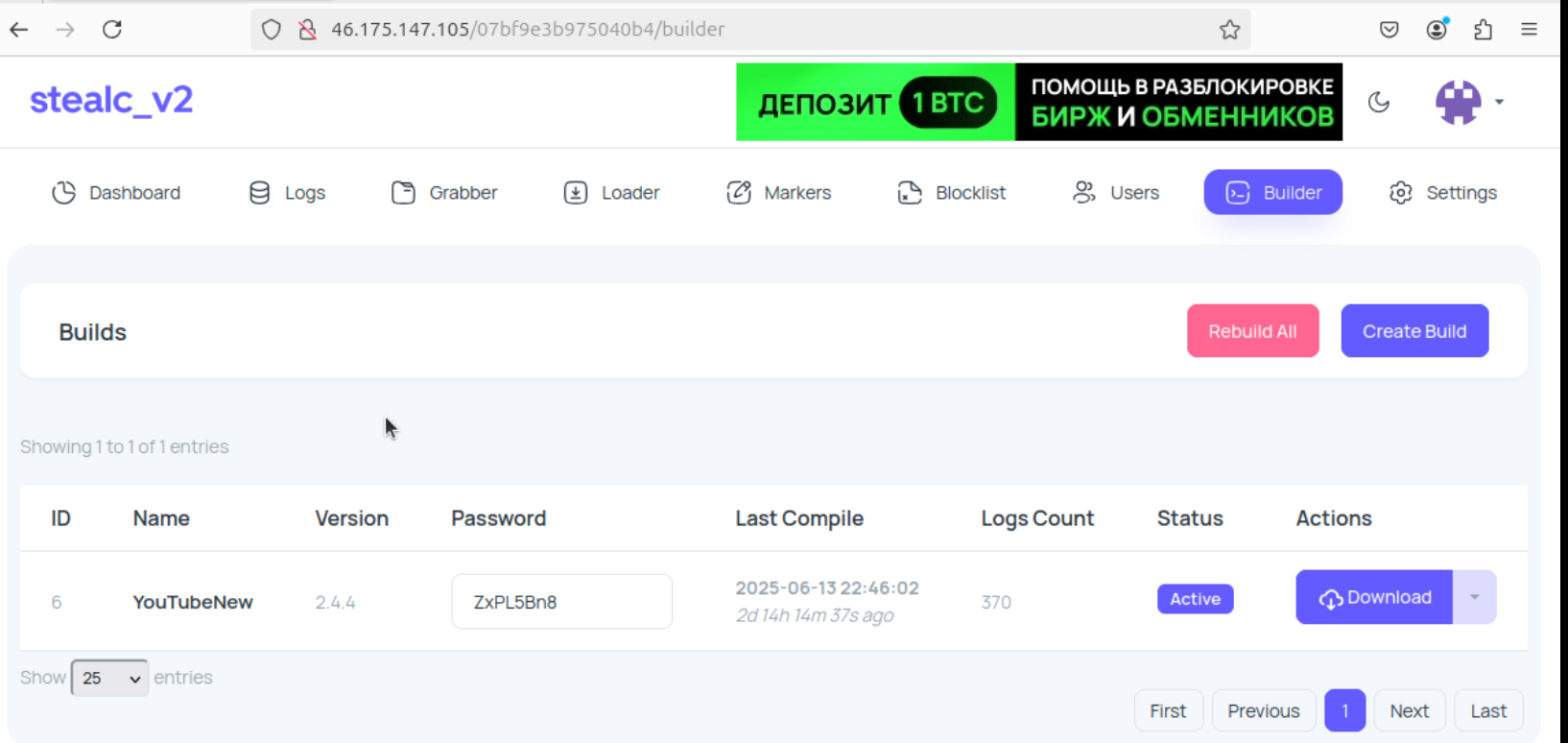

For several months in 2025, samples of StealC were circulating with conspicuous build IDs, identifiers created by the StealC operators to help them distinguish between campaigns. The build ID names included YouTube, YouTube2, and YouTubeNew (see Figure 1). Since the observed build IDs primarily relate to YouTube, we will refer to this threat actor as YouTubeTA, an abbreviation for YouTube Threat Actor.

YouTubeTA had over 5,000 logs stolen by StealC on their C2 server. The logs, based on the panel data, contained over 390,000 stolen passwords and more than 30 million stolen cookies (although most of these were tracking cookies and other non-sensitive cookies).

Figure 1. StealC build page with example build called “YouTubeNew.”

The names of the different builds made us suspect that YouTubeTA was somehow spreading the malware through YouTube. Conveniently for us, the StealC malware takes screenshots when it runs and sends the screenshot to its C2 server. By exploiting the XSS vulnerability we mentioned earlier, we were able to observe activity associated with the C2 server and what the victims were doing when StealC ran. In many cases, the victims were on YouTube looking for cracked versions of Adobe Photoshop and Adobe After Effects (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cropped image from C2 Server showing the victim searching for cracked Adobe Products on YouTube.

Curiously, most of the YouTube channels being abused to distribute StealC had several legitimate-looking videos posted a relatively long time ago, making the channels appear more reputable. The channels often had thousands of subscribers. However, there were long periods of inactivity between the legitimate videos and those promoting cracked software. YouTubeTA was likely using StealC to take over old YouTube accounts, which they then used to promote new samples of StealC.

Figure 3. Markers page from YouTubeTA’s StealC web panel.

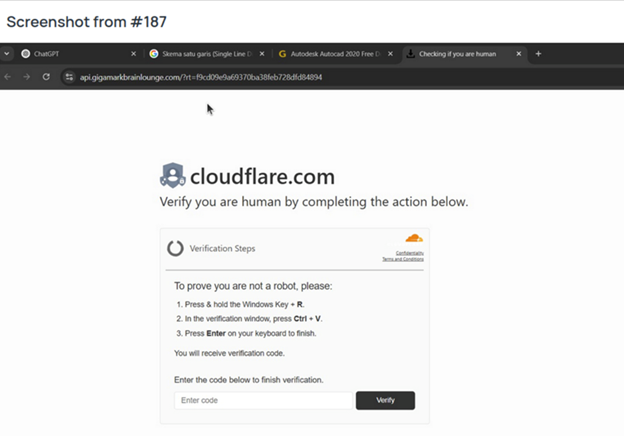

The StealC web panel has a feature known as “markers,” which allows users to highlight stolen credentials from specific domains, based on various categories they define. This feature probably helps sift through stolen credentials to identify interesting victims. We can see in Figure 3 that studio.youtube.com is given its own category. This subdomain of YouTube is specifically meant for content creators, providing tools to manage their YouTube channels. The fact that YouTubeTA was highlighting credentials stolen specifically from YouTube content creators adds credence to the idea that they may be looking to hijack old YouTube accounts to promote their malware. Notably, some of the screenshots we’ve seen show attempts at using clickfix technique (Figure 4), a social engineering technique that gained popularity in 2025, so the threat actor isn’t limited to infections through YouTube.

Figure 4. Likely clickfix page used to install StealC.

Attributing a StealC operator via panel fingerprinting

Some readers may have noticed by now that we have been referring to YouTubeTA as though they’re a single person rather than a group of threat actors. We’ve been able to gather a fair number of indicators suggesting that YouTubeTA is a single threat actor operating the web panel, and we’ve even been able to get a rough idea of their likely region.

The data we gathered can be categorized into five main types which include panel users, hardware fingerprinting, supported languages, time zones, and IP addresses.

Panel users: The most basic clue, YouTubeTA is a single person, comes from the StealC panel itself. The StealC panel features a function that enables operators to create multiple users and distinguish between admin users and regular users within the panel. In the case of YouTubeTA, however, we only see a single user: Admin. Interestingly, we haven’t seen any cases where multiple users were created, suggesting that the feature may see limited use.

Hardware fingerprinting: Another piece of evidence indicating a single user was identified through hardware characteristics. The screen width and height were constant across all cases when our XSS payload was triggered. Similarly, we utilized the JavaScript feature to determine which WebGL renderer is being used. For YouTubeTA, the renderer type told us that they use an Apple Pro device with an M3 processor. Again, this was consistent across all triggers of the payload, suggesting that YouTubeTA is a single threat actor.

Supported languages: In addition to helping us identify that the threat actor was a single person, our fingerprinting also allowed for some geolocating of YouTubeTA. Starting with supported languages, we know the threat actor’s machine supports both English and Russian. This alone wasn’t especially informative. Most machines support English, and since most MaaS are advertised on Russian speaking forums, it’s not a big surprise that YouTubeTA speaks Russian too. (Notably, the languages were a lot more informative with other StealC operators we managed to analyze. We’ve found supported languages ranging from Italian to Hindi.)

Figure 5. European Time Zones, Eastern European Summer Time in Beige (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern_European_Summer_Time#/media/File:Time_zones_of_the_Greater_Europe.svg).

Time zones: Yet another geolocation feature we can utilize is the time zone. The time zone on YouTubeTA’s machine was GMT+0300 (Eastern European Summer Time). This helps narrow down the country where YouTubeTA is likely from. Eastern European Summer Time helps exclude many countries where Russian is commonly spoken, such as Russia itself, as well as Central Asian countries like Kazakhstan. Naturally, the time zone also helps exclude countries where Russian isn’t widely spoken.

IP address: Of course, the most obvious feature to use for geolocating YouTubeTA was the IP address used to access the web panel. As one might expect, being such an obvious target for researchers, most StealC operators use VPNs when accessing their web panels. YouTubeTA also used a VPN most of the time, but fortunately, it seems they fumbled a couple of times.

In mid-July 2025, our XSS payload triggered on their panel, sending us the same fingerprinting information as in previous rounds. However, this time, the IP address wasn’t detected as a VPN by the tool we were using. VPN detection tools aren’t 100 percent accurate, so we tried several to confirm that the address is valid. The address was associated with a Ukrainian ISP called TRK Cable TV, which is consistent with our previous findings that YouTubeTA likely comes from an Eastern European country where Russian is commonly spoken.

Operational lessons: MaaS fragility, OPSEC failures, and identity abuse

As we’ve seen, YouTubeTA, despite being a single operator, was dangerously successful. They’ve stolen hundreds of thousands of credentials from thousands of victims around the world in just a few short months. This is a clear demonstration of why many threat actors employ the MaaS model. By delegating much of the work to other groups, they can specialize and have a more significant impact, much like in traditional industries. The success of YouTubeTA highlights the importance of identity security, as it’s terribly simple to do a tremendous amount of damage.

At the same time, there is a cost to cybercriminals using MaaS models. By relying on others to develop their infrastructure, threat actors become vulnerable to the same kind of supply chain risks regular industries struggle with. The StealC developers exhibited weaknesses in both their cookie security and panel code quality, allowing us to gather a great deal of data about their customers. If this holds for other threat actors selling malware, researchers and law enforcement alike can leverage similar flaws to gain insights into, and perhaps even reveal the identities of, many malware operators.

Further information on cookie security:

- Endpoint Credential Theft: How to Block and Tackle at Scale

- Crumbled Security: Unmasking the Cookie-Stealing Malware Threat

- How to Prevent Cookie Hijacking, A CyberArk Labs Webinar

- On-Demand: No More Cookies for You: Attacking and Defending Credentials in Chromium-Based Browsers

Ari Novick is a malware researcher at CyberArk Labs.