Synthetic Identity: When AI and ML Crunch (Your) Harvested Data

ChatGPT knows a lot about Len Noe, CyberArk’s resident technical evangelist, white hat hacker and biohacker. The biohacker piece of his title is a nod to the fact that Noe is transhuman (you might call him a cyborg and be right), which is why his grandkids call him “Robo Papa.”

ChatGPT knows all of this.

That’s because Noe fed everything he could find about himself that’s publicly available on the internet and by way of open source information technology (OSINT) into ChatGPT, all for the sake of cybersecurity research. These inputs included places he’s lived, auto registrations, utility bills, social media posts and transcripts of presentations he’s given and interviews he’s done. If it’s out there in the digital world, Noe plugged it into ChatGPT. What he wound up creating is a digital version of himself – what he refers to as his synthetic identity.

And, as Noe explains it, this synthetic identity – the identity that’s born from the blurring of physical and digital characteristics used to identify individual human beings – is permanent. The more you share online, wherever and however it may be, the more breadcrumbs you leave for attackers to someday, somehow use for nefarious purposes.

This is why Noe has created his own synthetic identity – as an extension of his ongoing effort to think like attackers – and, in doing so, stay a step or more ahead of them. “I was actually able to interact with a digital version of myself that had understanding, as well as information about my physical existence,” he told me in a recent episode of CyberArk’s Trust Issues podcast.

Screen captured video of Len Noe combing for his own publicly available information via OSINT.

Feeding Harvested Data into ChatGPT for Synthetic Identity Creation

At first blush, Noe’s ChatGPT experiment seems like doxing – the malicious act of curating and publishing identifiable information about a person or organization on the internet without their consent. But there are two big differences. First, the synthetic identity Noe created is based on his own personal data, and second, ChatGPT’s AI engine has the superhuman processing power to fuse disparate data points together instantaneously.

“All those little bits and pieces of [personally identifiable] information are spread out across multiple, different databases, so it’s very hard to make correlating points between them,” Noe says. “But if you take all of that information and put it into ChatGPT – something that’s main intended purpose is to find those types of correlations…” Noe trails off, but the implications are clear. Machine learning (ML), powered by artificial intelligence (AI) can make all sorts of connections about a person, and in doing so, expose them to significant risk.

In feeding all of that unprotected, harvested data into the ChatGPT blender, the output could take doxing to the next level. And the readily accessible opportunities for attackers lie in a swelling digital ocean of identities. The data correlations made possible through AI can make it much easier for attackers to deduce potential targets’ passwords and recovery questions. In a blink, AI can extract or deduce your mother’s maiden name or the street you grew up on – or most any typical standard question/answer for self-service recovery portals. And once it has that information, let the games begin.

Screen captured video of Noe interacting with his synthetic identity after inputting lots of his own publicly available data into ChatGPT.

Simple data extraction is just the tip of the AI iceberg, as it were. Attackers, of course, won’t (and don’t) limit themselves to what’s available. Our digital lives make it easy for the likes of advertisers and social media platforms to build composites of people’s identities based on their online behaviors and preferences. These digital dossiers are routinely sold and shared – and can also be intercepted.

This is how the potential for next-level, primo opportunities arise for attackers. Just think of the imitation opportunities alone. The creation of a synthetic identity can fuel spoofing, phishing and impersonation, by aiding attackers in producing more realistic human speech and text patterns and, in turn, convince someone to share or do something they shouldn’t. Once that’s been obtained, cyber extortion can enter the fray. The more personal data attackers can harvest, the more successful they are likely to be – and the more they will try to take.

“Think about the information that could be accessed with the data collected by the big tech miners,” Noe says. And, of course, as practitioners of “assume breach,” we must think about it. Data science, he says, requires thinking outside the box, problem-solving and analytical thinking. Attackers take a similar approach.

Noe adds, “Everything is asking our physical identities to attach more and more digital services to our digital identities. Every time we add a new app to our mobile devices another piece of software is asking for permissions to reach deeper into our private lives. Our individual attack surface is literally everywhere.”

Everything Ties Back to Identity

Noe acknowledges the potential for this new type of synthetic identity threat is yet to be fully realized. But as a cybersecurity practitioner whose job requires him to put himself in an attacker’s shoes, he’s constantly considering potential threats and ramifications. And they almost all inevitably involve data and identity.

Putting it into context, Noe says, “We hear about identity theft, identity monitoring, identity validation and identity security. Everything’s tied to identity and with good reason. Our identities are the most valuable thing we possess – it’s our likeness, our voice, behavior patterns. It’s our friends, family, hobbies, likes and dislikes. It’s what makes us.”

Your individual identity is an amalgamation of your physical and digital self, he contends. By this reasoning, your identity could potentially be put at risk through not just online interactions, but also how you interact in the physical world – like with your intelligent refrigerator or how you connect to home Wi-Fi, to point to just a couple of seemingly hundreds-to-zillions of other linked actions. We’re at the point where there is no separating these two sides of self – they are inextricably merged.

Who is Len Noe? Identity as a Guiding Principle

Let’s acknowledge again that Len Noe is transhuman by way of implanted chips and devices. Not that there’s any such thing as an ordinary human identity – we all have our own singular defining features and characteristics. But the tangled irony of focusing on the subject of identity with Noe is that his own identity is inherently complex. As we’ve chronicled here on the CyberArk blog and on our podcast in the past, Noe’s implants are for the sake of attacker-like experimentation – he doesn’t just think like an attacker, he’s altered his actual physical being in an ongoing effort to stay ahead of them. But you wouldn’t know it to look at it.

I’m standing with Noe as we await entrance to the Boston House of Blues for a company party capping Day Two of CyberArk’s IMPACT23 conference. It’s a mild early evening in May, amid a protracted New England spring that seemingly wants to Benjamin Button its way toward winter. Noe’s wearing short sleeves, revealing tattooed sleeves on both arms. We’ve spoken in the past about the various microchips and other implanted devices (with varying functionality) he has beneath his skin, but this is the first time I’m experiencing them, as he pinches his skin so I can see a couple of them silhouetted beneath the surface.

To get into the House of Blues, Noe flashes a standard-issue ID and an event-only wristband, just like all the standard-issue human attendees.

The Work-Life and Home-Life Identity Overlap

Work happens everywhere, anywhere. This means that, among other things, lines separating “work” devices and online identifiers from “personal” ones are blurred or have completely vanished. And attackers know this.

“As an attacker, why would I go after your corporate asset that I know has multiple layers of security controls on it, when I know you’re conducting business activities on an unprotected personal device?” says Noe. “It’s much easier for me to just target your own computer – then I can just ride the applications in the private tunnels back to the enterprise.”

Company-owned devices also present risks. “What’s the first thing that’s going to happen when a work laptop walks out of a corporate environment? It’s going to be connected to a home WiFi network,” Noe says. “Once these things leave the corporate environment, they’re out in the wild and it’s up to security professionals to keep security in the front of users’ minds so they remain vigilant, realizing everything out there is trying to get in and that they play an important role in keeping them out.”

Synthetic identity could come into play in a variety of ways within this context. For instance, a synthetic identity could be used to subvert a corporate network by way of the home network using data correlated through AI. Or, that synthetic identity could spoof individuals to cough up passwords for personal accounts that might be similar to (or exactly the same as) those used for corporate applications. Like, let’s say you were successfully phished and shared your Netflix password, which happens to be the same password you use for your enterprise Office 365 account.1 Game over. Although, of course, it’s not a game.

Stop Spreading Digital Breadcrumbs – Secure Your Digital Identity

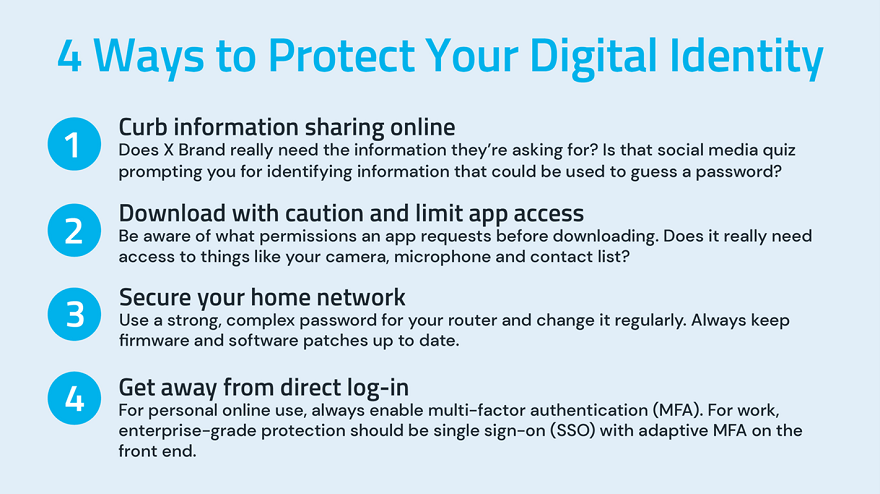

So, what can individuals and organizations do to stem the threats posed by AI and ML-assisted synthetic identities? Noe suggests the following:

Noe stresses that for MFA, “The best option we have is a true adaptive multifactor to validate that I am the person that I say I am. Multifactor does not mean two-factor – two is a minimum. And from an enterprise perspective we need to start looking deeply into the crossover between personal and business.”

With individual identities comprised of countless digital data points that are ultimately tied to physical beings, everything is more connected than it’s ever been. And now there’s widely available technology to connect the dots at scale. In a time considered to be an AI gold rush, while the technology itself is still at a relatively early stage, securing our identities, at work and home – everywhere – is paramount.

David Puner is a senior editorial manager at CyberArk. He hosts CyberArk’s Trust Issues podcast.

For more from Len Noe on synthetic identity, check out his recent Trust Issues podcast conversation.

1 You know not to repeat passwords, so please don’t do it. Check out this blog post for an eye-opener on password protection.