Ransomware Is Why Healthcare Endpoint Security Needs Urgent Care

Throughout the pandemic, a wave of ransomware attacks disrupted operations in healthcare organizations around the world. As frontline workers fought to keep patients alive, many documented records by hand and struggled to deliver effective care in the absence of electronic patient health information (ePHI) and lifesaving, internet-connected medical equipment.

Universal Health Services, which operates 400 hospitals and facilities in the U.S. and U.K., suffered a particularly devastating blow in an attack that wiped out IT systems, postponed treatment and elective procedures, ultimately causing $67 million in lost revenue and reputation damage. After ransomware extortion took down Oregon-based Sky Lakes Medical Center’s systems, the hospital refused to pay the requested ransom but announced it would need to replace more than 2,000 computers and servers to “start fresh.” And an attack on a German hospital forced accident and emergency departments to close. An ambulance transporting a patient suffering from an aortic aneurysm was diverted to another hospital, delaying her treatment by an hour. She died shortly after. Later, prosecutors would launch a negligent homicide investigation, saying the ransomware attackers were to blame.

“If we don’t break the back of this cycle, a problem that’s already bad is going to get worse,” former Acting U.S. Deputy Attorney General John Carlin told the Wall Street Journal a few months ago. Looking back on the first half of 2021, this was a harbinger of things to come.

Interconnected Healthcare Systems: Highly Vulnerable Targets

Healthcare data has long been an attractive target for attackers. Hospitals and other private healthcare organizations routinely store ePHI records, which include personally identifiable information (PII). These records must be compliant with many regulations and standards such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Yet due to widespread resource constraints and legacy system limitations, many health records are stored without proper security protections. And unlike other industries, healthcare organizations cannot delete patient records after specified periods of time; they must remain accessible (and secure) forever.

As portals to this sensitive data, the computers used within hospitals and healthcare systems are also major attack targets. Industrial-grade medical computers are often wheeled around the hospital floor by doctors and nurses to efficiently order and administer drugs, control medical devices that perform imaging scans or tests, and display diagnostic images and lab results. In many medical practices, computers are stationed in every room, giving providers fast access to ePHI records and facilitating communication among team members. And in operating theaters, computers play a critical role in pre-surgery planning, image visualization, patient monitoring and even robotic-assisted procedures.

Attackers are not stopping at commandeering these critical computers and servers. They’re also reaching for medical IoT devices with increasing frequency. For example, the WannaCry ransomware attack infected 1,200 diagnostic devices, and many more were taken offline to stop the spread.

While increasing ePHI, computer system and IoT device interconnectivity is helping providers transform the way they deliver care — adding even more challenges to the growing list of cybersecurity concerns.

When Downtime Isn’t an Option

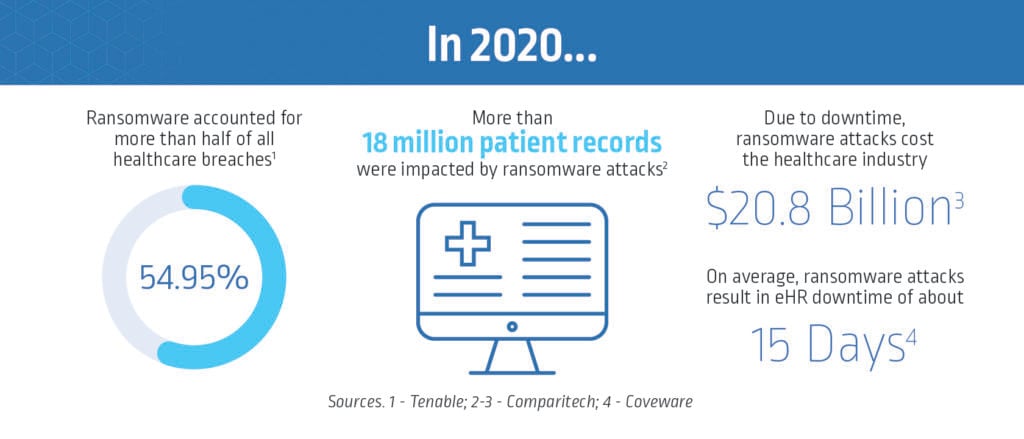

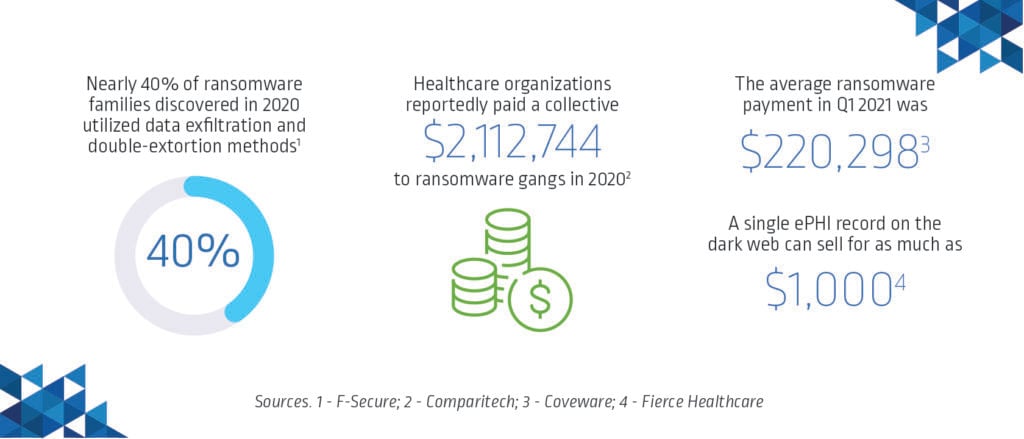

Whether politically or financially motivated, attackers understand that in the business of life and death, healthcare organizations simply cannot afford to negotiate for days or weeks while their systems are held hostage. It’s estimated that ransoms totaling $15.6 million were demanded of U.S. healthcare organizations alone last year and that organizations paid a collective $2,112,744 to ransomware gangs. In reality, the total is likely much higher than what has been publicly reported. But even when organizations pay the requested ransom, there’s no guarantee that healthcare systems will be restored — or that the attackers won’t come back for more.

Operator-Based Ransomware and Double-Extortion Demands on the Rise

Ransomware attacks begin by exploiting configuration gaps and access vulnerabilities to deliver malware. These are often accomplished by using ransomware-as-a-service kits (ready to use and easy to find on the dark web) to infect unpatched systems using common phishing techniques, drive-by malware downloads, known public exploits or brute-force credential theft.

Yet over the past several months, CyberArk Labs and the CyberArk Red Team have tracked a significant rise in operator-based ransomware attacks that look a lot different than these opportunistic “spray and pray” attempts.

Operator-based ransomware attacks are executed by highly skilled threat actors who can target — and react to — the specific attack surfaces of a specific organization. In many cases, these attackers operate in stealth mode for extended periods of time, utilizing advanced TTPs to find and steal credentials for both cloud and on-premises infrastructure — especially those with elevated admin privileges on endpoints, such as Microsoft Windows or MacOS administrator accounts. Unfortunately, it’s no secret that in the healthcare industry, working as a privileged user (for example, a doctor making their rounds with a tablet that can access numerous patients’ medical records) or allowing a third-party vendor (for example, an insurance company or medical equipment supplier) to access a privileged system is all too common.

The attackers’ next objective is to harvest credentials for even higher privilege escalation and lateral movement, looking for more machines and more valuable data to extort. Once they’ve gained the necessary privileges, they often take the following steps:

- First, they exfiltrate large amounts of sensitive data, such as PII.

- Then, using high levels of privileged access and to avoid detection, they look for ways to “live off the land.” They take advantage of pre-installed programs and processes on a compromised endpoint that authorized privileged users, such as system admins, utilize often. By using the victim’s own tools against them, attackers appear legitimate, making it difficult for security teams to identify malicious activity. Plus, attackers don’t have to bother building or distributing new tools, which takes time and resources, and can raise red flags.

- Finally, they execute their ransomware kit using built-in software distribution channels that the organization trusts and uses routinely. This is a highly effective tactic, as it allows the attackers to disable – or sometimes completely circumvent – existing security controls such as endpoint detection and response (EDR) or extended endpoint detection and response (XDR) tools.

Pay Up (Again) – Or We’ll Leak Your Patient Data, Too

During their attacks, ransomware threat actors look for ways to stealthily disrupt backups, delete shadow copies and unlock files to maximize their impact. In many virtual hostage situations, attackers will not only demand a ransom payment for decrypting target data but also threaten to leak it unless additional payment is made. According to F-Secure research, nearly 40% of ransomware families discovered in 2020 utilized such double-extortion methods.

Just last month, the FBI issued a report on a spike in Conti ransomware attacks targeting U.S. healthcare and first-responder networks. According to report authors, “If the ransom is not paid, the stolen data is sold or published to a public site controlled by the Conti actors. Ransom amounts vary widely and, we assess, are tailored to the victim. Recent ransom demands have been as high as $25 million.”

We’ll Be Back

You can also count on these savvy ransomware operators to think ahead. During their privilege escalation efforts, they often leave backdoors or hidden identities so they can re-enter the victim’s environment in the future. The U.K.’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) recently shared a cautionary tale of an organization that paid millions in bitcoin to recover its files but failed to take necessary steps to identify the attack’s root cause and secure their network. As a result, the same attackers came back just two weeks later, using the same techniques to re-deploy the same ransomware, forcing the organization to pay the hefty ransom again.

How Healthcare Can Stay Ahead of Ransomware Attacks

As ransomware attacks become more sophisticated and highly targeted, healthcare organizations recognize the need to proactively ramp up their security posture to protect critical infrastructure and preserve patient care and trust.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and HIPAA guidelines provide prescriptive recommendations to help strengthen defenses — and all echo the importance of least privilege, access and identity restrictions as the core foundation for a modern cybersecurity program based on Zero Trust.

That’s why identity-centric controls are so important to incorporate as part of a defense-in-depth endpoint security strategy, along with EDR and XDR, next-generation anti-virus (NGAV), data and network analysis, threat hunting and incident response tools. Not only can Identity Security solutions help detect and block the malware itself, but by “trusting nothing and verifying everything” they also work to stop identity and privilege abuse at critical points in the attack chain. As a result, threats can be found and stopped before they do harm. Once these controls are in place, healthcare organizations can focus on enhancing cybersecurity awareness and skills training, revisiting digital security fundamentals and hardening and backing up critical hospital systems to protect against future attacks.

To learn how your healthcare organization can reduce the endpoint attack surface by combining least privilege, ransomware protection, application control and other identity-centric capabilities, read our new eBook and get a jump-start with CyberArk Endpoint Privilege Manager – our SaaS solution proven to protect against 3 million strains of ransomware and counting.